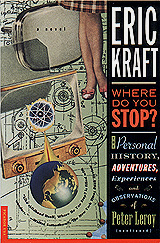

| Where Do You Stop?

Chapter 6: The Confusing Midgame in Chinese Checkers |

by Eric

Kraft, as Peter

Leroy

|

YOU CAN READ THE FIRST THIRD

YOU CAN BUY THE

|

First, at some time during the summer we must have passed a boundary between childhood and adolescence, without even noticing it. I had had some vague realization of this as soon as I entered this new and larger school building. I felt that I was suddenly expected to be, in some way that I did not understand, newer and larger myself, more grown-up, more responsible. That was unsettling enough in itself, I’m sure, but time’s longer view shows me now that it was compounded by the fact that when I looked for models of the grown-up and responsible behavior that the seventh grade was apparently going to require of me, I looked, more closely than ever before, at my parents, and I began to come to see—again, only vaguely—that they were imperfect models, quite possibly unequal to the puzzling demands of the seventh grade. Second, I discovered to my surprise that the kids of Babbington came in a far broader range of shades of beige and brown than I had previously realized. I had known birches—and ashes and oaks—but now, in that instant when I came through the front door of the new building, the range was extended to include boys and girls of teak and mahogany and walnut. Here was a bunch of my contemporaries whom I’d never seen before. Where had these browner boys and girls been all this time? I think I realized—I think we all realized, at some level below words—what this surprising broadening meant: there was more to Babbington than we knew. Immediately, the unsettling question arose: how much more? How do we measure the size of our ignorance, after all? We don’t know how much we don’t know until what we don’t know becomes what we didn’t know; that is, after we know it; and then we know only how much we didn’t know compared to what we know now—we still don’t know how much we don’t know. This was the first lesson of the seventh grade, taught the moment I came through the door. It might as well have been chiseled into the terrazzo that had been so thoroughly cleaned and polished for opening day. Before that moment, I suppose I thought, if I thought about it at all, that I had Babbington pretty well figured out. Now here was new evidence of my ignorance. Sometimes my youth seems to have been devoted entirely to the accumulation of such evidence. Here was the revelation of a new world. I felt disoriented, much as I imagine a fifteenth-century peasant would have felt if he’d been handed a map at the center of which was something other than his little village, the center of his world. I remember well another feeling that came with this new knowledge. I was annoyed. I didn’t like the idea that I had been kept in the dark or the notion that I was now expected to make sense of this larger world on my own. It seemed a lot to ask of a kid my age. I had begun kindergarten before I turned five and had skipped the third grade, so I was only ten-going-on-eleven. Perhaps, I asked myself, it would be possible to take another shot at the sixth grade and confront these puzzles next year, when I had matured? Not likely. Third, there was imposed upon us a baffling new nomenclature. This frightening change made everything we were to study seem like an unfamiliar subject. Arithmetic had become “mathematics,” and the word provoked an immediate mental image for me: a tightly wound spring, straining, powerful, dangerous. Reading had become “literature,” and there was considerable disagreement about how we were even supposed to pronounce it. Science had become “general science,” suggesting something vaster than science alone, as if everything we had studied so far had been confined to a small corner of a huge map now being fully unfolded for the first time. The blackboards of the old school were absent from the Purlieu Street School. In their place were devices much like them—extensive flat things mounted on the walls, meant for writing—but these were green. What were we supposed to call them? Greenboards? Green blackboards? Why had this change come about? The official explanation was that yellow chalk on a green board would be easier on our eyes. To Raskol, that seemed unlikely. “They’re trying to confuse us,” he said, and he sighed and shook his head slowly, as if his suspicions about the true purpose of school had finally been confirmed by these green blackboards. (Years would pass before chalkboard became the general term, and during the intervening period of uncertainty the nation’s youth, innocent victims of a summertime revolution in the technology of wall-mounted writing surfaces, sat puzzled through millions of student hours pretending to listen to geography and geometry but unable to stop asking themselves, “What the heck should I call that thing on the wall?” In the years since that time, I have found myself repeating Raskol’s assessment more and more frequently, in more and more settings. When I arrive at an airport, for example, frantic and sweaty, certain that I’ve missed my flight, and a smiling young woman in the uniform of the airline tells me that snow flurries at an airport half a continent away mean that my flight won’t be leaving for two hours, Raskol appears before me, just as he was in the seventh grade. He shakes his head, he sighs, he holds his hands out in helplessness. “See?” he says. “They’re trying to confuse you.”) Fourth, and possibly most bewildering of all, we were made to change classes. When our day’s bout with one subject had ended, we got up and left the room, and went to another, similar, room where we tussled with another, different, subject. What an enormous change this was. In the past, when we had spent nearly the entire school day in one room, we had drifted from one subject to the next, one blending slightly with the next, like the indistinct edges of objects depicted in a watercolor painting, but the act of changing classes said, “There is definition here. Crisp lines separate one subject from another. The boundaries of knowledge are sharp and can be marked precisely,” and here I am at the edge of my theme. Mark Dorset, my sociologist friend, has said that one of the ways people can be divided into two camps is according to whether they exhibit a tendency to stay put or a tendency to move on. The difference between staying-put behavior and moving-on behavior is, he says, profoundly indicative of essential personality traits. Well. There we were, after six years of staying put for most of the school day, now required to move on every forty-eight minutes. A personality change was being imposed on us. We would be sitting in a classroom, stable and studious, and then a bell would ring, triggering a brief, intensely active period, a burst of frantic energy, when we all changed our positions, rushing into the halls like photons scattered from a naked light bulb, like particles of dust puffed into the air, or like a multicolored bunch of marbles in the confusing midgame in Chinese checkers. |

|||

Here are a couple of swell ideas from Eric Kraft's vivacious publicist, Candi Lee Manning: Tip the author.

Add yourself to our e-mailing list.

|

Where Do You Stop? is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, dialogues, settings, and businesses portrayed in it are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 1992 by Eric Kraft. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Where Do You Stop? was first published in hardcover by Crown Publishers, Inc., 201 East 50th Street, New York, New York 10022. Member of the Crown Publishing Group. YOU CAN BUY THE

For information about publication rights outside the U. S. A., audio rights, serial rights, screen rights, and so on, e-mail the author’s imaginary agent, Alec “Nick” Rafter. The illustration at the top of the page is an adaptation of an illustration by Stewart Rouse that first appeared on the cover of the August 1931 issue of Modern Mechanics and Inventions. The boy at the controls of the aerocycle doesn’t particularly resemble Peter Leroy—except, perhaps, for the smile. |

|

||||||

| . | . |